Origins of Japanese Tea Ceremony

The Japanese tea ceremony, known as chanoyu or sado, possesses a rich history deeply intertwined with Japanese culture and spirituality. Interestingly, its origins lie not within Japan itself, but across the East China Sea. This means that the elegant ritual we now associate with Japanese tea culture evolved from a distinctly different practice.

Early Influences from China and Zen Buddhism

Initially, tea arrived in Japan through the efforts of Buddhist monks studying abroad in China. Recognizing tea's medicinal properties and its capacity to enhance meditation, these monks carried tea seeds back to their homeland. For instance, Eisai, a renowned Zen Buddhist monk, is widely credited with planting the first tea seeds at Kennin-ji temple in Kyoto during the late 12th century. This event marked a crucial turning point, establishing tea cultivation in Japan and paving the way for the eventual development of the tea ceremony.

Evolution into a Japanese Cultural Practice

From these monastic beginnings, tea drinking gradually permeated Japanese society, extending beyond the temple walls. Over time, it gained popularity among the warrior class and the nobility. These early adopters initially utilized tea for its medicinal value, but later embraced elaborate tea gatherings as a means of displaying their wealth and social standing. However, the 16th century marked a significant shift in the history of the Japanese tea ceremony. Influential figures like Sen no Rikyū emerged, transforming the ceremony by emphasizing simplicity, humility, and the aesthetic of wabi-sabi – finding beauty in imperfection. Rikyū's impact shaped the tea ceremony into the profound spiritual and artistic practice we recognize today. He introduced key elements such as the small, rustic tea room (chashitsu) and the nijiriguchi, a low entrance designed to symbolize humility irrespective of social rank.

This transition towards simplicity and spiritual contemplation redefined the tea ceremony, moving it away from ostentatious displays of wealth and grounding it in Zen Buddhist principles. Furthermore, the increasing use of Japanese-made teaware and utensils, rather than imported Chinese ones, further solidified the tea ceremony's unique Japanese identity. Learn more in our article about The Origin of Japanese Tea Ceremony. As a result, the modern tea ceremony has become more than just drinking tea; it is a holistic experience encompassing art, spirituality, and social interaction, reflecting a fascinating blend of foreign influence and Japanese innovation.

Tea Room Architecture and Design

The emphasis on simplicity and introspection also profoundly influenced the design of the spaces where the tea ceremony takes place. The tea room, or chashitsu, evolved into a meticulously designed sanctuary, embodying the ceremony's core principles. Picture a space carefully crafted to encourage self-reflection and a deep appreciation for the present moment – this is the essence of the chashitsu.

Key Elements of the Chashitsu

Several key elements contribute to the unique atmosphere of the chashitsu. These features are not mere decorations, but integral components, each holding symbolic meaning and practical purpose.

- Tatami Mats: These woven straw mats form the floor of the chashitsu, providing a soft, natural surface and dictating the precise movements and seating arrangements. They contribute significantly to the quiet and tranquil atmosphere.

- Tokonoma: This alcove serves as the heart of the tea room. It typically features a hanging scroll with calligraphy or a simple flower arrangement, reflecting the current season and the spirit of the gathering. This focal point directs guests' attention towards beauty and contemplation.

- Nijiriguchi: The small, low entrance serves as a potent reminder of humility. All who enter, regardless of social status, must bow low, symbolizing equality within the tea room.

- Roji (Garden Pathway): The path leading to the chashitsu is more than just a walkway; it is a carefully designed transitional space. It separates the outside world from the serene environment of the tea room. Stone lanterns, thoughtfully placed stepping stones, and meticulously raked gravel cultivate a sense of anticipation and encourage guests to release their worldly concerns.

This careful design creates a holistic environment conducive to mindfulness and appreciation. Every detail, from the texture of the tatami mats to the placement of a single flower, contributes to the overall experience. This emphasis on aesthetics and the creation of a sacred space elevates the tea ceremony beyond simple tea drinking, transforming it into a spiritual and artistic practice. The chashitsu itself becomes a tangible expression of the ceremony’s philosophy.

Tea Ceremony Steps and Rituals

While the tea room provides the setting, the ceremony itself unfolds through a precise sequence of steps and rituals. This carefully orchestrated order, passed down through generations, transforms the simple act of drinking tea into a deeply meaningful experience. This highlights the fact that the tea ceremony is not just about the tea itself, but the mindful preparation and consumption of it.

Welcoming and Purification

The ceremony commences with guests purifying themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths at a tsukubai, a stone basin in the garden. This act symbolizes cleansing oneself of the outside world before entering the sacred space of the tea room. Guests then proceed along the roji (garden path), its carefully designed elements further aiding their mental and emotional transition. This preparation is essential for fully embracing the tranquility and focus of the tea ceremony.

Entering the Tea Room and Initial Formalities

Guests enter the chashitsu through the nijiriguchi, bowing low as they pass through the small entrance. Once inside, they admire the tokonoma with its carefully selected scroll or flower arrangement, reflecting the season. For example, a single sprig of cherry blossom might grace the alcove in spring, while a stark, elegant branch might be displayed in winter. The host then serves a light confection, known as kaiseki, which complements the tea and enhances its flavor. This gesture signifies the beginning of the formal tea preparation.

The Heart of the Ceremony: Preparing and Serving Matcha

The central act of the tea ceremony is the preparation and serving of matcha. The host meticulously prepares the matcha, using precise movements to scoop the powdered tea into the bowl, add hot water, and whisk it to a frothy consistency. Each gesture is imbued with meaning, reflecting grace, respect, and mindfulness. The way the host cleans the tea utensils, for instance, is not simply for hygiene but also a symbolic act of purification. The first bowl of thick tea (koicha) is shared among the guests, symbolizing unity and connection. Afterwards, thinner tea (usucha) is served individually to each guest. The guests admire the tea bowl, noting its craftsmanship and design, before partaking in the tea.

Concluding Rituals and Farewell

After the tea is finished, the host cleans the utensils, and the guests are invited to examine them closely. This demonstrates respect for the tools and the artistry involved in their creation. Finally, the guests depart, expressing their gratitude to the host for the experience. The tea ceremony, therefore, unfolds as a profound ritual, a journey inward, and a powerful expression of Japanese culture and spirituality.

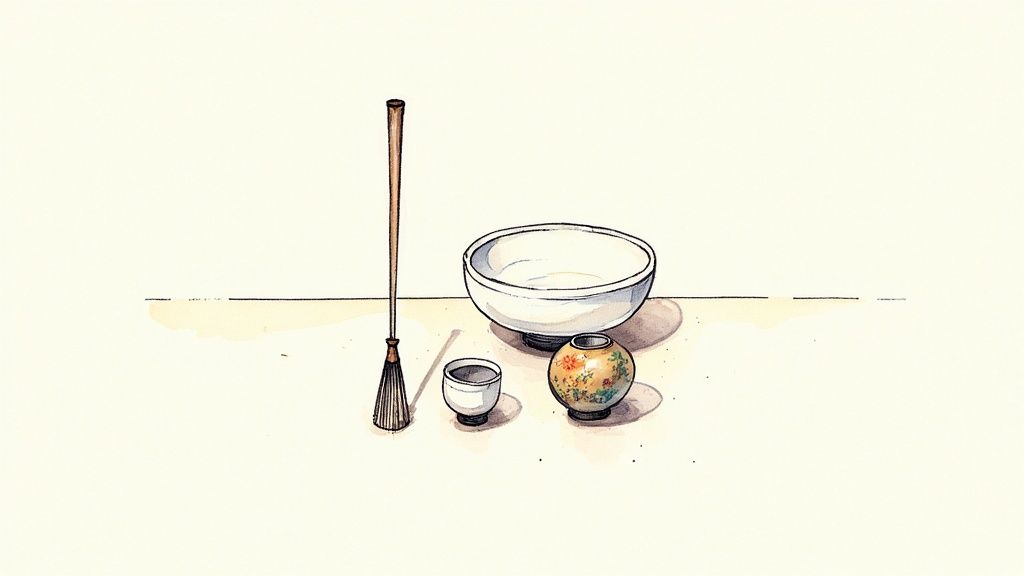

Essential Tea Ceremony Tools

The Japanese tea ceremony is deeply connected to the specialized tools used in preparing and serving matcha. These tools are not merely functional; they hold symbolic meaning and aesthetic value, reflecting the ceremony's focus on simplicity, mindfulness, and appreciating the present moment. This signifies that understanding the tea ceremony requires an appreciation for the tools that facilitate it.

Key Utensils for Matcha Preparation

The preparation of matcha involves a few key utensils, each playing a vital role. These tools are often crafted with meticulous care, reflecting the reverence for the ceremony.

- Chashaku (Tea Scoop): Crafted from bamboo, the chashaku measures the precise amount of matcha for each serving. Its delicate shape and natural material enhance the ceremony's aesthetic. The gentle curve of the chashaku, for example, ensures a graceful scoop.

- Chawan (Tea Bowl): The chawan is more than just a vessel; it is a work of art. Often handcrafted and unique, each chawan is admired for its individual characteristics, adding a sensory layer to the ceremony. Furthermore, the chawan's size and shape influence the tea's temperature and aroma.

- Chasen (Tea Whisk): Also made from bamboo, the chasen whisks the matcha and hot water into a frothy emulsion. Its finely crafted tines ensure a smooth consistency. Whisking is not merely practical, but a rhythmic movement contributing to the ceremony's meditative quality.

Other Important Tools

Other tools also contribute to the overall experience and flow of the tea ceremony, reflecting the meticulous attention to detail that permeates every aspect.

- Chakin (Tea Cloth): This small linen cloth wipes the chawan clean, symbolizing purity and attention to detail. This seemingly simple act adds to the ceremony's meditative and cleansing aspects.

- Kansu (Water Jar): Used to hold the hot water for the matcha, the kansu can be made from various materials. It represents the importance of water in the ceremony.

- Natsume (Tea Caddy): This small, typically lacquered container stores the matcha powder. Its elegant design reflects the reverence for the tea itself. Some natsume feature intricate decorations, adding to the artistic dimension of the ceremony.

These specialized tools are integral to the tea ceremony, contributing to its aesthetic, symbolic, and spiritual dimensions. They enhance the sensory experience and encourage mindfulness, elevating the act of drinking tea to a profound ritual.

Types of Tea and Seasonal Considerations

The Japanese tea ceremony is deeply connected to the specific types of tea used and the seasonal variations incorporated into the ceremony. Just as the tokonoma displays seasonal flowers, the choice of tea and the ceremony's details harmonize with the rhythms of nature. This means the tea ceremony is not a static ritual, but a living tradition that adapts to the changing seasons.

Matcha: The Heart of the Ceremony

Matcha, finely ground powdered green tea, is the cornerstone of the Japanese tea ceremony. Its vibrant green color and rich, umami flavor are highly valued. Matcha's unique properties make it ideal for the ritual; for instance, the whisking process creates a frothy texture that enhances the sensory experience. The two main types of matcha used are koicha (thick tea) and usucha (thin tea). Koicha, with its thick consistency, is often served during formal ceremonies, offering a more intense flavor. Usucha, being thinner and slightly less intense, is suitable for less formal occasions.

Seasonal Variations in Tea and Ceremony

The tea ceremony embraces the changing seasons, incorporating seasonal elements into both the tea selection and the specific details of the ritual. In spring, lighter, fresher matcha varieties might be chosen, reflecting the season's vibrancy. The tokonoma might display cherry blossoms, and the sweets served might have delicate floral flavors. Summer brings a focus on refreshing coolness, with lighter teas and chilled sweets. The tea room might feature elements like bamboo or wind chimes. This adaptation continues throughout the year, with autumn's warm colors and earthier teas, and winter's stark beauty and the comforting warmth of the charcoal brazier.

While matcha remains the primary tea, other types, such as gyokuro and sencha, might be served on occasion. However, matcha's unique qualities and symbolic importance remain deeply intertwined with the ceremony. These subtle adjustments to the tea and the ceremony reflect a profound connection to nature.

Modern Practice and Cultural Significance

The history of the Japanese tea ceremony has significantly shaped its modern practice, influencing its role in contemporary Japanese society and its growing global presence. While the core principles of simplicity, humility, and harmony remain central, the ceremony has adapted to the modern world in several ways. This connection to the past informs our understanding of the present-day practice.

The Tea Ceremony in Contemporary Japan

In modern Japan, the tea ceremony still holds cultural significance. It's practiced by people of all ages and backgrounds, although its role has evolved. It's an important element of traditional Japanese arts, taught in schools and community centers, ensuring that younger generations connect with this rich heritage. The tea ceremony also plays a role in social and business settings, for welcoming guests, fostering relationships, or celebrating occasions.

Global Influence and Adaptation

Interest in the tea ceremony has grown internationally. Tea schools and workshops offer opportunities to learn the rituals and history worldwide. As the tea ceremony spreads across cultures, it naturally undergoes adaptations. While some practitioners adhere to traditional forms, others incorporate elements from their own cultures, creating hybrid forms that reflect the local context.

The Future of the Tea Ceremony

The future of the tea ceremony will likely involve a balance between preserving tradition and adapting to change. Some practitioners are exploring ways to make the ceremony more accessible to younger audiences, potentially incorporating technology or modern design elements. Regardless of how it evolves, the tea ceremony will likely continue to provide a valuable space for reflection, connection, and appreciation for the present moment.

Interested in experiencing the richness of matcha and Japanese culture? Visit matcha-tea.com for a deeper dive into the world of matcha, its health benefits, delicious recipes, and the captivating culture it comes from.